Live Streaming every show!

Refresh your browser to catch a show in progress!

Visit our Facebook page or YouTube channel!

But nothing beats being in the room with the music & the musicians!

Help us pay the band!

653 Chenery Street in San Francisco's Glen Park neighborhood

Open to walk-in trade and browsing Tuesday to Sunday noon to six

phone: 1-415-586-3733 email: [email protected]

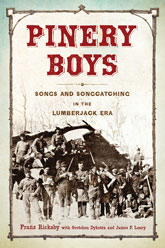

Pinery Boys:Â Songs and Songcatching in the Lumberjack Era (University of Wisconsin Press, 2016)

Pinery Boys:Â Songs and Songcatching in the Lumberjack Era (University of Wisconsin Press, 2016)

A newly annotated edition of a landmark 1926 collection of lumberjack song published by pioneering song collector Franz Rickaby, augmented by a biographical essay and additional songs.

“Franz Rickaby was the first to put the singing lumberjack into an adequate record and was of pioneering stuff. … His book renders the big woods, not with bizarre hokum and studied claptrap … but with the fidelity of an unimpeachable witness.”

–Carl Sandburg

Gretchen Dykstra, granddaughter of Franz Rickaby and editor of this edition of his original 1926 book, Ballads and Songs of the Shanty Boy, will talk about her grandfather’s work and her quest to find the grandfather she never knew through a time and place she never experienced. Her biography of her grandfather, whom she called Frenzy, is included in this volume.

Gretchen Dykstra, granddaughter of Franz Rickaby and editor of this edition of his original 1926 book, Ballads and Songs of the Shanty Boy, will talk about her grandfather’s work and her quest to find the grandfather she never knew through a time and place she never experienced. Her biography of her grandfather, whom she called Frenzy, is included in this volume.

____________________

Pinery Boys: Songs and Songcatching in the Lumberjack Era, published by the University of Wisconsin Press in its series “Languages and Folklore of the Upper Midwest,” incorporates, commemorates, contextualizes, and complements Franz Rickaby’s landmark 1926 collection of lumberjack songs Ballads and Songs of the Shanty Boy.

Included in Pinery Boys is a biography of Rickaby by his granddaughter, Gretchen Dykstra, who co-edited Pinery Boys with James P. Leary. Here, Dykstra comments on her quest to find the grandfather she never knew, tracing his steps through the Upper Midwest:

“Although I’m a New Yorker now, I’ve always liked the Midwest. When I was seven I spent the summer swinging from barn beams into haystacks at my grandmother’s dairy farm in Fort Atkinson, Wisconsin. My father was born in Grand Forks, North Dakota. He, my mother, one sister, and I all graduated from UW–Madison, and my step-grandfather, Clarence Dykstra, was its chancellor. But it took me sixty years to write about the Midwest—and then it was thanks to Bill Zinsser, my late, great writing teacher.

“When Bill went blind, he stopped writing and teaching formally, but he met individually with some writers in his rambling Manhattan apartment. I was one of the lucky ones. I went about once a month. If I came at noon I’d bring him a sandwich; if I came at 2:00 I’d bring him cookies. That was the deal. He’d sit at the dining room table, sunglasses and baseball cap on, and listen intently as I read my latest pages. Occasionally, he’d stop me and, in his inimitable, funny, but always supportive way, would offer an editorial suggestion.

“’Gretchen, if you are a bus driver going from New York to Miami, you can’t head to Chicago without telling your riders why.’ Then I’d know I had an organizational problem.

“It was Bill who urged me to go looking for the grandfather I never knew—Franz Rickaby, who had died when he was only thirty-five. My grandmother had called him Frenzy. As a young English professor at the University of North Dakota, Franz wandered the Upper Midwest from 1919-1923. With a fiddle on his back, he sought the songs of the shanty boys from the camps of the quickly disappearing white pine forests.

“His resulting songbook was published by Harvard University Press several months after he died in 1926. The book became a minor classic in the world of American folklore and folksong. Edited by George Lyman Kittredge, praised by Carl Sandburg, and celebrated by Alan Lomax, Rickaby’s book was unique for the lyrics, the tunes, and the vivid portrait he painted of the lumberjacks and their lives.

“I took Bill’s advice and hit the road. I traced Rickaby’s footsteps—as many as I could—and, in doing so, I met my grandfather. And I came to know a slice of American history from the lumber industry to the forest fires, from cutover land to the last remaining majestic white pines. I dove into the files of archives and historical societies from Galesburg, Illinois, to Ladysmith, Wisconsin, to Virginia, Minnesota, and points in between. When I called eminent folklorist Jim Leary, who knew Rickaby’s work well, a new edition of my grandfather’s work took shape. Pinery Boys was born.

“It has four parts: Rickaby’s original text with all the lyrics, music, and his lively notes; an introduction by Leary, placing Rickaby in historical context; additional never-before-published songs that Rickaby collected, with notes by Leary; and the story of my own quest and discovery of who Rickaby was, what he might have seen, and what motivated him.

“One man, one life, a glorious time, a changing landscape, and three voices.”

TAKE OUR SURVEY

To take our SURVEY, click here, and help the BBCLP get to know you better! As Duke Ellington always said, we love you madly...

The Bird & Beckett Cultural Legacy Project

Our events are put on under the umbrella of the nonprofit Bird & Beckett Cultural Legacy Project (the "BBCLP"). That's how we fund our ambitious schedule of 300 or so concerts and literary events every year.

The BBCLP is a 501(c)(3) non-profit...

[Read More ]

The Independent Musicians Alliance

Gigging musicians! You have nothing to lose but your lack of a collective voice to achieve fair wages for your work!

The IMA can be a conduit for you, if you join in to make it work.

https://www.independentmusiciansalliance.org/

Read more here - Andy Gilbert's Feb 25 article about the IMA from KQED's site